Late on Sunday afternoon, doing some research on whether recipient countries might pay lip service on Rule of Law/justice sector reform donor programs, I came across this article in the Mexican Law Review on Rule of Law, titled, “International Support for Justice Reform: Is It Worthwhile? written by Luis Pásara, a Peruvian lawyer, sociologist and professor.

I have just skimmed through it, although I already know I want to study it in full because certain premises of his coincide with some of my thoughts. While it addresses justice reform in Latin America, the author touches on universal problems. Mr. Pásara’s conclusion is worth quoting:

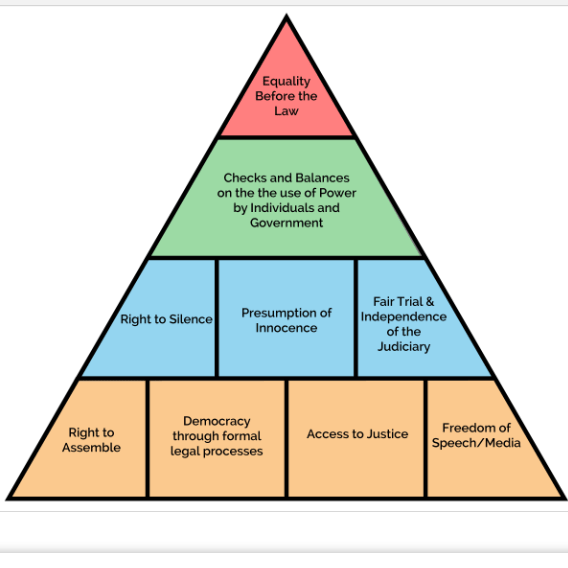

On the one hand, it is important to keep in mind that establishing the Rule of Law is a broader and more difficult task than reforming the justice system. Therefore, building a better justice system is not enough to establish the Rule of Law; the former is just a component of the latter. The quality of the laws, the legal culture, the actual social and economic inequalities, and the role played by the government —among other elements— are important and complex components of the process of building the Rule of Law.

On the other hand, internationally-funded programs of justice system reform are not able to produce deep changes, which are badly needed for both a better justice system and the establishment of the Rule of Law, in the receiving countries. Clearly, such programs are not able to “fundamentally reshape the balances of power, interests, historical legacies, and political traditions of the major political forces in recipient countries. They do not neutralize dug-in antidemocratic forces. They do not alter the political habits, mind-sets, and desires of entire populations” and “[o]ften aid cannot substantially modify an unfavorable configuration of interests or counteract a powerful contrary actor.”175 That is why international aid in the area of justice has not delivered a new justice system in receiving countries. It simply could not do it.

But there is some room for improvement. Taking into account the analysis made in this article, some concrete suggestions can be proposed for the many people, acting in good faith in the international agencies and who are willing to find ways to do a better job of improving justice systems in the region:

- —

Knowledge is a must. No decision about the area, content, size, timing or amount of a project should be made without detailed knowledge of the subject in the country where the work is to be done.

- —

Learn what others produced. To gain knowledge of the prevailing conditions mainly requires: collecting the information that already exists, paying attention to national actors’ perceptions and analysis, taking advantage of the knowledge of international experts who have gained experience in that particular country, and evaluating other agencies’ experience in the field.

- —

National actors and a clear strategy are needed. The conditions required to develop a project include: a core of national actors who are truly committed to the reform goals, and a strategy —to be designed jointly with national actors— with well-defined short, medium, and long-term goals within the project.

- —

National actors have a crucial say. The implementation phase of any project needs to have a partnership of national and international actors, but the last word should be said by national actors who know better and ultimately are responsible for the reform process in their country.

- —

Monitoring and evaluation are indispensable. Project implementation needs continuous monitoring and project evaluation presents opportunities to learn about both achievements and failures. External reviews of the projects —including work done by academic researchers— are powerful tools for a critical analysis on what works and what does not. Reticence to share information with capable peers is, in the long term, a way of wasting resources.

If these remedies —and other possible changes— are introduced to alter the performance of international actors and agencies, they may dramatically increase the level of quality of the outcomes of justice reform projects.